Timeless Classic

![]()

Timeless Classic |

|

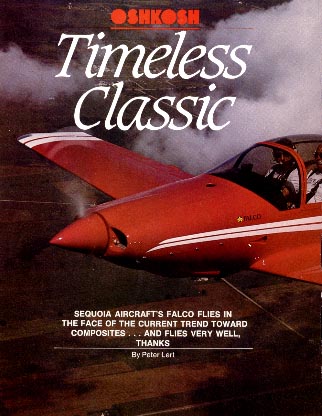

Sequoia Aircraft's Falco flies in the face of the current trend toward composites... and flies very well, thanks.

by Peter Lert

|

This article was published in the November 1986 issue of Air Progress. |

Consider, for a momemt, the impact of composites on sport aviation. With the exception of the Swearingen SX-300, virtually all the new high performance designs are based on composite construction materials, replacing the more traditional methods of bygone years.

Did you ever stop to think, though, what a composite really is? The vast majority of current composites are, as their name implies, a combination of two or more elements designed to take advantage of the structural properties of each. For example, what we generally call "composite" is more accurately called "fiberglass reinforced plastic," in which a fiber material (in this case, glass) chosen for its tensile or compressive strength is aligned with the load paths and held in position by a matrix of tough but amorphous material, in this case epoxy resins.

Composites have been around for a long time, however -- in fact, since long before Burt Rutan and his followers started using them for light aircraft. Let's look at a more traditional composite: In this one, fibers of cellulose, which provide tensile strength, are held in position by a matrix of tough material called "lignin," which replaces, and in many ways is similar to, epoxy resin. The resulting composite material, when properly used, is similar to fiberglass/epoxy composites in that it is light, strong, stiff, easily worked, and immune to fatigue. Unlike most epoxy composites, it is also essentially unaffected by ultraviolet light, and does not lose significant structural strength when heated beyond room temperature. While we could correctly refer to this wonder material as "cellulose reinforced lignin composite," most engineers and aircraft designers refer to it by a somewhat more convenient name -- wood.

Now wood may seem to some to be a rather old-fashioned material. Perhaps it is -- but there are some things that are still best made out of it. For example, no one has ever found a better material for the construction of violins; the finest instruments in history were made by Antonio Stradivari. No less Italian, no less wooden, and of no less sophistication is the subject of this pilot report: The Sequoia Falco kit plane.

Of course, the Falco (Italian for "Hawk") didn't start out as a kit. It was designed some thirty(!) years ago by Stelio Frati, the same man to whom we owe such fabulous aircraft as the Marchetti (now Agusta) SF.260. In fact, the "SF" in the designation represents Signore Frati's initials*, and in many ways the SF.260, fabulous though it is, is little more than a scaled-up Falco. The original Falcos were built by Aviamilano* and remain avidly sought after by well-heeled European sport pilots. On the other hand, given the economic exigencies of postwar Italy, with its well-known changes in government ("...if this is Tuesday, I think the Socialists are in power, or is it the Communists or the Christian Democrats?..."), the Aviamilano project languished, and the Falco became more or less dormant. By the time things had, if not improved, at least stabilized to the point where a market for that class of airplane had reappeared, wood had become somewhat passe, and S. Frati had revamped the design to come up with the SF.260.

Meanwhile, however, over on the continent that some misguided Italian had discovered, while blundering around in search of India, the homebuilding movement was in full swing. One of its proponents, a hot bluegrass musician called Alfred P. Scott, liked little European two-place ships -- in fact, he even owned a boxy little postwar Messerschmitt 209 "Monsun." On the other hand, years of singing about life in the piney woods of the South may have suggested to him that they could be used to make airplanes out of, so he started a company called Sequoia Aircraft and designed a couple of nifty two-place ships, basically side-by-side and tandem variants on the same planform. The Sequoias were wooden*, of course, and were designed to be high-performance two-place cross-country and aerobatic machines.

I honestly don't know whether the design of the side-by-side version of the Sequoia was based on that of the Falco; after all, Alfred was aware of Frati's masterpiece, and imitation is the sincerest form of flattery. In any case, while quite a few sets of Sequoia plans were sold, no actual airplanes were built... and in the meantime, the rights to the Falco became available. Alfred obtained them, with the thought that the ship would make a terrific homebuilt.

Indeed, it would-in fact, has-but not quite in the way Alfred may have envisioned. The original drawings were suited to series production, with extensive tooling and special fixtures: "...'ey, Luigi, pass me the spar splice scarf gauge fixture...." Complex subassemblies such as landing gear actuators were vendor items not originally built by Aviamilano, and now unavailable. As a result, Alfred found himself compelled to completely redraw the plans, an undertaking of a magnitude comparable to redesigning the airplane from scratch. In the process, he also developed an illustrated builder's manual about the size of a medium telephone book.

At about the same time, such people as Frank Christensen, designer of the Eagle, were establishing the market for top-quality, top-dollar kits. It began to look as if this would be the best way to market the Falco, and this has proved to be the case: While you can still build one with nothing more than the awesome $400 set of plans, unless you have the resources and experience of a cabinet-maker and machinist, you'd be far better advised to purchase one or more of the complete series of kits now available from Sequoia Aircraft. Those with extensive woodworking skills, equipment, and experience might opt to buy only machined metal parts such as the landing gear or control system, but most Falco builders appear to opt for the complete package, with major wood parts subcontracted out to Trimcraft of Lyons, Wisconsin. The "full house" kit, which includes about everything but paint, glue, the engine, and the radios, currently costs $42,500. Add the engine (a 160-hp Lycoming O-320 is recommended, but you can opt for a 180-hp O- or IO-360) and basic IFR equipment, and you're looking at somewhere between 60 and 70 grand by the time you're done, somewhere around 1500 to 2000 hours later.

This isn't cheap, of course, but for quite a few people what you get is worth every cent: A two-place that turns heads everywhere it goes, can cruise around 190 KTAS with the 160-hp engine, and is massively overbuilt without being heavy. This is not a bad idea, either, because the combination of performance and handling that is as close to perfect as anything I've ever flown result in pilots tossing the airplane around with what, in its native land, is called "brio." You'd have to be pretty close to redline to be even close to the limits; anywhere in the normal operating range of the airplane, the worst you could do while yanking on the controls would be to stall it while still far short of its structural limits.

I had last flown a Falco a few years ago, when I had a chance to fly an elderly factory-built Aviamilano* version that Alfred had brought to the United States to use both for personal transportation and as a "master copy" while developing the plans. Although I was impressed then, Alfred had told me to wait until flying one of the kit versions; indeed, the old blue and yellow factory bird is now known as the "corporate disgrace," and is carefully kept as far as possible from Oshkosh to avoid giving potential kitbuilders the wrong idea. This time around, I was lucky enough to fly in the Ferrari-red ship built by former Air Force pilot Karl Hansen of Sacramento, California -- arguably the best of the current crop.

In some ways, the Falco looks old-fashioned, but it's the same way in which, to continue the analogy, a Ferrari 275GTB4 looks old-fashioned compared to the newer ones. Remember, readers, that this airplane was designed in an era when screen stars looked more like Gina Lollobrigida than Twiggy, and by the same token both cars and airplanes of the era make their later-day counterparts look as awkward and angular as those Japanese "Transformer" toys.

Of course, much of the design was dictated by aerodynamics, and some areas have been changed since the Aviamilano days. The current cowling, for example, is fiberglass and far sleeker than the rather crude sheet metal version on the first ships, with the underslung carburetor intake replaced by a flush NACA scoop. The basic lines, though, remain the same, with the wing tapering to semi-rounded tips and an unabashedly tail-shaped tail rather than some stylist's "jet-style" swept fin. Many of the recent Falcos, Karl's included, have a sleek lower-than-standard "Nustrini" canopy, named after the Italian air racer who first put one on his Falco; this costs a couple of inches of headroom, but Karl must be over six feet and doesn't appear to have any trouble.

Real airplanes, of course, have sliding canopies, and this one is no exception. Getting in is a matter of climbing up on the wing (I was terrified of damaging the immaculate paintwork with my usual klutzy boots, but lucked out this time) and letting yourself down into the seats while suspending your weight from the windshield frame and/or cockpit sides. The seats are fairly low but not excessively reclined; for our test flight, I had to stuff the folded canopy cover in behind me, since the sliding adjustment mechanism was jammed on my side, but when it works pilots from Karl's size on down to small women can be accommodated comfortably; the seats move up a bit as they're slid forward.

Real airplanes also have sticks, with the Falco unit a fairly short one that curves up between your knees to clear the front of the seat. The standard kit has a central quadrant with lever-type throttle, prop, and mixture controls, but it appears simple to add a second throttle on the left side wall to let you fly with your right hand on the stick and left hand on the throttle even in the left seet. A center console between the seats has the emergency landing gear extension controls, just as in the SF.260.

One of the shortcomings of many homebuilt designs is that you find gorgeous airplanes in which panel design and layout seems to have been an afterthought. Not so with the Falco; the standard panel includes flight instruments in the standard T arrangement on the left side, engine instruments on the right including very compact and professional cluster gauges for engine condition monitoring, and the radio stack in the center. The most complete package available includes fully aerobatic gyros and such goodies as a digital fuel totalizer, all with standardized installation packages from Sequoia. This is more important than you might think, particularly with a complex and well-equipped airplane like the Falco: On the average homebuilt, only about half the builder's man-hours goes into actual structural buildup, with the remainder going to detail work, systems installation, and finishing. Even such a seemingly simple task as installing, say, a hydraulic line is made much simpler if you have plans showing you where and how each bend in the tubing should be made.

The instant I advanced the throttle to takeoff I knew this was going to be fun. Even with two aboard and about half fuel, acceleration was impressive, and only the slightest back pressure at about 70 knots was required to rotate and lift off. With the gear in the wells the Falco surges upward at close to 1500 fpm; in fact, throughout our photo flight we found ourselves with a very significant performance reserve over the T-6 that Budd Davisson was using as a camera platform.

In a way, it's hard to describe the controls or handling of the Falco, because like those of the SF.260, they're almost "not there." By this, I mean that everything is so nicely balanced and harmonized that you don't really recognize the presence of the controls at all; you fly the airplane "through them." It's almost as if you can direct your flight path without conscious thought; I suppose the most concise definition of the controls would simply be "just right."

If the Falco's handling has any shortcoming, it's in terms of stability as an instrument platform for IFR cross-country work. Not that it isn't stable -- it is -- and the light, precise controls would make "maneuvering intensive" tasks such as an instrument approach a pleasure. For long-term IFR cruise, however, the airplane's willingness to go exactly where you point it means that you must be at pains to point it only where you want to go! I'd want at least a wing leveler in any Falco used for extensive travel, and there's no reason one can't be installed.

One of my favorite ways to explore the handling of a new airplane is to fly a photo mission with it, since my attention is directed almost totally outside. Here, once again, the precision and lightness of the Falco's controls were impressive; it was perfectly easy to respond to Budd's typically finicky and niggling commands ("... move four feet forward and two feet down....") without even having to think about them.

Once away from the photo ship, I had a chance to fiddle around a bit more. Steep turns are, like almost everything else in the ship, effortless; even at 60 degrees bank pitch forces are light enough to obviate the need for trim. The stall, while a bit sharper than that of the typical production Spam can single, is completely honest and predictable whether executed straight ahead or in a turn.

The fact that I was sitting loosely on the wadded canopy cover, and couldn't cinch the belts down tight, precluded anything in the way of heroic aerobatics, but experience in other Falcos suggests that they're very rewarding. A complete Christen inverted fuel* and oil system is one of the approved Falco options. During a clean letdown, the ship is not particularly eager to shed speed, but it's perfectly tractable in the pattern once the gear is down. With the three wheels in the breeze, drag is almost doubled, and good-sized flaps make it easy to mix in among the 150s. Eighty knots over the fence is more than adequate and the trailing-link main gear massages the ego, rather than the coccyx, in the event of a firmer-than-desired touchdown.

It's difficult to compare the Falco with many of the current crop of high-performance kit planes. The design is, after all, some thirty years old, and like its construction material, wood, it's been around for a long time (perhaps that's why Alfred Scott chose to name his firm after the Sequoia, a similarly long-lived all-wood design). On the other hand, it has nothing to apologize for in the way of performance, handling, or comfort -- and, if you go to the full-kit route, it's probably no harder to build than many of the "Glass Manegerie." In fact, if I personally had to choose a homebuilt in this class for myself (fat chance, the way aviation writers get paid!), I'd lean strongly toward the Falco if for no other reason than that I am quite allergic to most epoxies.

There's a lot more to it than that, though. While I have nothing at all against some of the recent designs -- some, indeed, I find both beautiful and exciting -- the Falco remains a classic in the truest sense of the word. Even in a world of 300-mph Fiberglass Rockets, it has a unique place, and one that I am sure it will continue to hold for years and decades to come.

|

|