Hung Nguyen

![]()

Hung Nguyen |

|

This article appeared in the March 2011 Falco Builders Letter. While it may have almost nothing to do with the Falco, except for the connection between Susan Arruda and myself, it's our website so we can put anything here we feel like. |

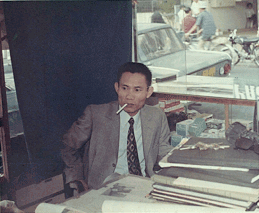

In Saigon office, 1970

In 1966, fresh out of college and right before going into the Marine Corps, I had a final dash of freedom in Europe, picking up a bright red Porsche 912 at the plant in Stuttgart, and then driving through Germany, Austria, Italy, France, Spain and finally to Paris, where I stayed with my father’s cousin Frederick E. “Fritz” Nolting. Cousin Fritz had been the U.S. ambassador to Vietnam, right before Henry Cabot Lodge, and he was working as a banker in Paris. He was an elegant Virginia gentleman who got caught up in the machinations, politics and power struggles that attend great moments in history. He knew I was probably headed to Vietnam with the war raging on, and one evening we had dinner at his spacious Avenue Foch apartment. It was just the two of us. I listened as he told me the story of what had happened in Vietnam during the Kennedy administration.

He talked about how the Kennedy administration was unhappy with President Diem, and how three men in the administration, Averell Harriman, George Ball and Dean Rusk wanted Diem out. They argued that he was a Catholic running a Bhuddist country, that there was nepotism with him bringing his brother Ngu into the government—an exact parallel of the Catholic U.S. President and his brother the Attorney General, but never mind that. In all the discussions, Lyndon Johnson was adamantly opposed to undermining Diem—in Texas, a contract is a contract. But he was overruled and the word quietly passed to the Vietnamese generals that it would be okay to remove Diem from power, but please don’t hurt him. The generals promptly shot Diem and his brother in a tank. Two weeks later, JFK was assassinated. Cousin Fritz went to see Johnson, and said “Why don’t you just say that President Kennedy was a great man but he made a great mistake.” “I can’t do that,” Johnson replied, “the man is now a martyr.” And so began the downward spiral of Vietnam and all of this story later came out in the Pentagon Papers.

Eleven years later and after going to Morocco, not Vietnam, in my military service, I owned an old Victorian apartment building in Richmond, and Susan Arruda was our manager. Our maintenance man was illiterate and temperamental, and his form of job security was to always keep everything not quite working so we were dependent on him whenever things started going wrong—which was a constant state of affairs. Susan and I decided to fire the man, so she ran blind advertisements in the local paper and interviewed the men in my partner’s office, some distance away. I remember it like it was yesterday. Susan walked into my office and said “You will not believe who walked through the door.” She said the man wore a blue suit and brought a three-page typed resumé—for an apartment maintenance job. He had an AAS Civil & Architectural Engineering degree, previous employment in a maintenance job at a local charity the Little Sisters of the Poor, and then I turned the page where his previous job was with a construction company in Hue, Vietnam. “This was my company” where Hung Nguyen—the man applying for our maintenance job—had employed 5000 people. It was a family business that was started in 1760 and had been run by many generations of his family. Mr. Nguyen was the head of the company and all of the family worked there and shared in the profit. Between 1960 and 1972, he was a subcontractor for two large U.S. companies which had contracts with the U.S. government. He built the Bien Hoa Highway, Cam Ranh, Chu Lai, Danang and Phu Bai air bases. He also constructed the combat base for the 101st Airborne division, and all the secondary roads from the DMZ to the Mekong Delta. His company designed and built various large projects for the Vietnamese government such as a cancer hospital and a soccer stadium in Saigon, the governor’s complex, a medical college, a university, and the renovation and rehabilitation of the King’s Palace in Hue, and also several large factories in Saigon, Danang and Hue. His head office was in Hue, where Diem had been a neighbor, and there were offices in five major cities.

And this man became our maintenance man in a 77-unit apartment building. He says he had never worked with his hands before, but he had a holster of tools on his hip and roamed the halls, tightening every loose screw and soon had the building in great shape. He said he had to forget all about the past, and that eight out of ten friends who were used to a life of luxury and servants had killed themselves. He is a quiet, shy man, and I can only tell you all this after much prodding over time to get it out of him. One day he was in my basement office where I had a world map on the wall—to help me think great thoughts—and he looked at the map of Vietnam, saying that he had a boat that he used to go back and forth between Hue and Vung Tau, a seaside port in South Vietnam. I was curious about the boat, and asked him how big it was. His hands stretched out, one in front and one behind him as if to measure the size of the boat, and then his hands dropped and he said “big boat.” I pressed him further and he went through the same thing, arms out, and then “big boat.” He knew of course, with precision how big his boat was, and after a couple more sessions like this, I finally asked him, “Mr. Nguyen, how big was your boat?” “A hundred feet.” And then he opened up. It was twelve feet wide, had twin Chrysler diesels, and had been designed for him by engineers in Taiwan and built of wood in the Mekong Delta for $33,000. And he went on to explain that he had the boat as insurance in case the communists took over, and when they did in 1975, he piled his children and family (a total of 42 people) on the boat and headed for Australia. He spent a couple of days offshore and confirmed that indeed the country had fallen. But when they had reached international waters, he was picked up by the U.S. Seventh Fleet, hauled to the deck in cargo nets and then taken to Subic Bay in the Philipines, later to Guam, and finally flown to an Army refugee camp at Indian Town Gap in Pennsylvania.

All 42 members of his family came to Richmond, sponsored by the Paul Nott family. He immediately went to work at their scrap metal company and then to the Little Sisters of the Poor where he worked as a maintenance man and dishwasher. Then he came to work for us for three years, working sixteen-hour days, from 7:30 to 3:30 at our building and then 3:30 to 11:00 at the Medical College of Virginia. There were many times when he would ask me to sign sponsorship papers to help get relatives out of Vietnam. He said I didn’t need to worry about this. I signed them all and there never were any problems. I think back now with embarrassment at the way some of my fellow Marines referred to the Vietnamese at the time, but when they arrived in our country, there never was an unemployment problem with the Vietnamese. Hung Nguyen became the leader of the Vietnamese community here in Richmond.

After three years with us, Mr. Nguyen got a job with Philip Morris, where one nine-to-five job paid him what the two jobs had brought in. He began work in an Associate Field Engineer, but it didn’t take Philip Morris long to recognize what they had. He was moved into the factory construction division, and then for the next 25 years, he was a project manager at Philip Morris, building factories all over the U.S. and Asia, in Kuala Lumpur, Manila and China. A typical plant was 200,000 square feet, cost a hundred million to build and took 12-18 months. Everything had to happen right on schedule, and it cost $3000 for each hour the plant was delayed. They paid well for the work but everything had to come in on time and on budget. A plant in Cabarus County, NC was a million square feet and cost $500 million. Mr. Nguyen retired in 2005, and I reconnected with him then. He now lives in Florida near two of his sons. He was 75 and looked 55 when he retired and Philip Morris tried to get him to stay on for another five years. He has five sons and two daughters, all college educated.

When Susan came back to work with me, we called him and asked him to stop by next time he was in Richmond. He’s now on the board of the Little Sisters of the Poor, where he once worked in maintenance and as a dishwasher. He stopped by the other day, and I want you to know, he now has a Falco hat.—Alfred Scott |

Susan Arruda and Hung Nguyen

Here is the article in pdf format

I will be happy to post any comments you send me here.—Alfred Scott I read the story of Hung Nguyen from beginning to end without stopping to breathe. Wonderful. George Larson Very nice article about Mr Nguyen. I was in the US Army Support Command in DaNang on China Beach in 1969-70. It was my job to prepare inter-service command briefings for I Corps. The impressive resilience and industry of the Vietnamese people through centuries of upheaval and war was, and is, remarkable. Refugees on China Beach would convert a "camp" to a functional village in a matter of weeks, creating market, temple, church, clinic, school and housing etc. from whatever was at hand—and then work hard to improve the place iteratively. Phil Loheed Beautiful story. I read it three times non-stop. Yassine Ouchchy Wow... great story! Thanks for this, Alfred! Steve Mouzon This is a story worth disseminating to all, especially today’s entitled folks. It is an inspiration to read of this man’s careful preparations for escape from Viet Nam, keeping his boat in readiness and taking his family onto the dangerous seas bound for Australia. I was especially moved to read that eight of ten friends in Viet Nam, accustomed to a life of wealth, took their own lives when disaster struck the entire country with a purge. This outstanding example of tough self-reliance could run for President—and win—if only he had been born in the US. Bev Williams It was a thoroughly enjoyable experience to read your profile or memoir of Hung Nguyen. Truly a remarkable human being and worthy of being well known in these xenophobic times we live in. "How could we let those g--ks come to the U.S., after what they did to us?" Has Hung Nguyen's story been more widely publicized than in your Falco news (which was good)? I hope so. I enjoyed your other profiles as well. Having them all in one place is a great idea. Gerry Cooper Mr. Hung Nguyen's story was uplifting and inspiring, and should serve as a role model for future generations. I could only find one obvious and objectionable error in the whole article and it was right at the beginning. This has everything to do with the Falco... He has a Falco hat! David J. Silchman Thank you so much for sharing that story about my father.

As you mentioned, he's a shy man and I've never heard that story myself.

It was a great read and I write this to you with tears in my eyes. Marguerite Nguyen Thank you for the story on my dad. His life story has always inspired and motivated me to be a better human being and I hope it will inspire others. Phil Nguyen |

|

|