First Flight:

George Barrett

![]()

First Flight:

|

|

by Alfred Scott

This article appeared in the September 1994 Falco Builders Letter. |

I wish every homebuilder in the U.S. could watch, as I did the other day, as Al Aitken takes an airplane through the flight testing process. For homebuilders who often see the first flight as a victory celebration cum wedding night, it's instructive to watch a real professional at work. You learn, first off, that the most professional test pilots are the most meticulously careful people in the world. They have no illusions of the risks involved, and the entire flight test methodology is intended to minimize the risk by testing each aspect of the airplane's handling in the safest possible manner.

Few people have had as much effect on the attitudes of homebuilders toward flight testing as Al Aitken. As many of you know, he's a graduate of the Navy's Patuxent River Test Pilot School, flew F.18s in the Marine Corps and was one of those who bombed Libya for President Reagan. Our F.8L Falco Flight Test Guide is really Al Aitken's work-all I did was write down what Al told me. This document has been widely circulated far beyond our circle of Falco builders, and it's been widely praised and religiously followed.

I was at the Gordonsville (Virginia) airport to witness the first flight of George Barrett's Falco. Al Aitken had arrived at 7:00 AM and when I got there at 10:30, he was still checking the aircraft over. After another half-hour of this, he started the engine, taxied over to the fuel pumps and then began the first of a long series of high-speed taxi tests.

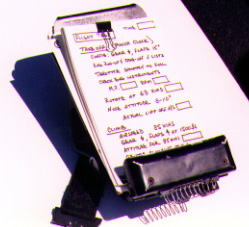

One of the many flight test cards.

First there was the directional control tests, to prove that the airplane would steer down the runway under takeoff power and then stop when brakes are applied. These were followed by the aileron control effectiveness test, to prove that each aileron worked, that both wings began to lift at roughly equal speeds. This also reveals any grossly out-of-rig condition in the wing.

(A friend of mine once built a two-place Quickie with wings so badly twisted that the airplane could maintain wings-level flight only with full right stick. The test pilot-supposedly qualified to do such testing-discovered this after breaking ground. He was lucky and was able to complete the pattern to the left, and landed safely. However, if the twist had been any worse, the airplane would have spiraled in after liftoff. This is a risk you avoid with the controls effectiveness tests. You discover the problem before leaving ground.)

George Barrett's engine was a freshly majored 160 hp IO-320-B1A with Cermi-chrome cylinders, and the break-in requirements were that the engine not be allowed to get very hot prior to the first flight. As a result, after each series of high-speed taxi tests, the engine was allowed to cool until you could put your hand on the rocker arm covers. The final taxi test checked the elevator effectiveness, and then we broke for lunch. The results of each test were carefully recorded on a series of flight test cards that Al had prepared for the flight.

George Barrett's 1969 Plymouth Satellite (nice catchy aviation name) and

his Falco.

Al carefully filled the Falco with the fuel required for the planned one-hour flight, plus a reserve, and then taxied out for takeoff. The engine runup was rough. The rpm drop on the left mag was excessive, so Al brought the plane back in. The bottom plug on the No. 2 cylinder was not firing, so it was removed and cleaned.

Once again Al taxied out to the end of the runway. This time the engine runup was fine, and he lined up at the end of the runway, applied full power and accelerated down the runway. He quickly chopped power and braked to a stop. The engine had stumbled briefly on the initial application of power. After much discussion, we decided this was probably due to a slightly over-rich condition coupled with other spark plugs slightly coated with oil.

We concluded that it made sense to lean the mixture slightly and try again. A freight train rolled by, and Al decided to let the train clear the area before taking off-it would, after all, be an unhappy experience to put the plane down on the tracks and then be run over by a train. After a few minutes, the train disappeared from sight and hearing, and Al began the takeoff. This time, the takeoff roll went normally, the Falco charged down the runway, rotated and flew off. We stood and watched as the Falco climbed straight out at a shallow angle, on and on until finally, after reaching perhaps 1500 feet, it banked gently to the left and circled back over the field.

"How does it feel", I asked George Barrett, a retired lawyer (trusts and estates; he can't stand litigation and fights) and builder of the white airplane that droned over our heads. "I don't feel anything," said George, who was far more concerned about Al Aitken's well-being and safety than the fate of his own airplane. As he spoke, I noticed that he was shifting his weight from left to right foot in a rapid, nearly running, frequency.

George Barrett watches as his Falco takes off for the first time.

For the next hour, we watched as the plane circled overhead. With each passing minute, we all felt a sense of relaxation. George had a hand-held radio, and we could hear the reports from Al Aitken in the plane. The airplane handled well. The engine was running fine, and Al read off the temperatures, pressures and other numbers on the engine.

After perhaps 15 minutes, Al began a series of shallow turns each way, timid 20-degree banks at a time when some homebuilders have already rolled their creations. Later he took the plane through a series of slow-flight maneuvers and nibbled at the stall. It all looked good. Then, after nearly an hour in the air, he lined the Falco up with the end of the runway, descended, flared and landed.

It was a moment best remembered for the sheer ordinariness of it all, a spectacular time mainly because nothing had gone wrong, and we were all overwhelmed more by a sense of relief than victory. No trumpets, heroic music or setting suns. Just Al Aitken taxiing over to the gas pumps once again before they put the plane away for the day.

Watching it all were George and Joy Barrett, their son David, Joel and Carolyn Shankle, Tom Prasec (a local mechanic who helped George) and me. There were smiles and handshakes all around. Joy and Carolyn were bursting with pride. We put the plane away and all headed home after a long day.

There was one other man there watching it all. A friendly, blond man who hovered on the periphery of our tiny group. I later learned that in addition to being a pilot, he was also the local funeral director.

George Barrett and Al Aitken.