Nobody Shoots at Me

![]()

Nobody Shoots at Me |

|

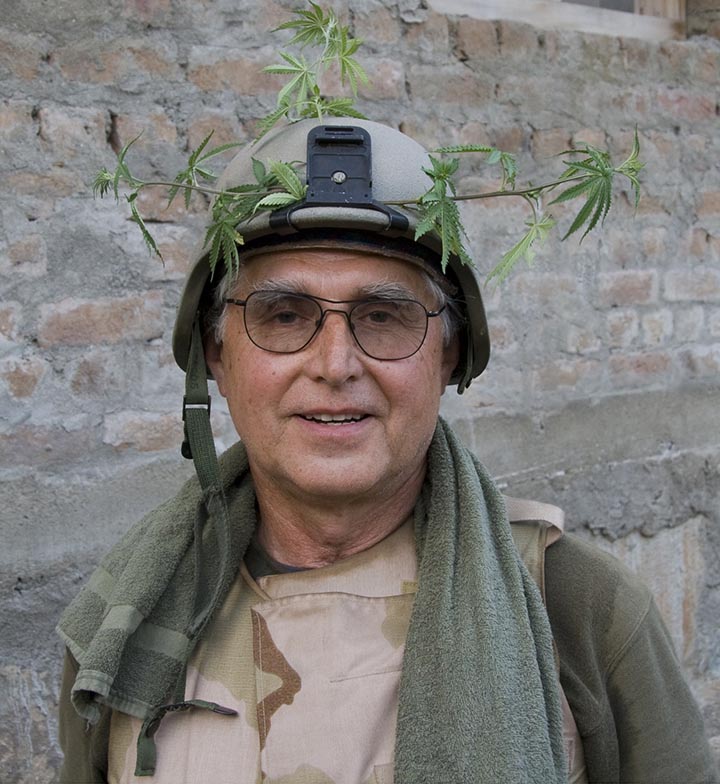

Jonas in the Kunar with enhanced camo headgear. Don't worry, no one smokes this stuff, which grows in every ditch.

by Jonas Dovydenas

All of the news organizations have cut back on their reporting from Iraq and Afghanistan, so it is the destiny and obligation of the Falco Builders Letter to make up for this. I have been to Afghanistan ten times and never once was I shot up or IEDeed, mortared or bombed. Not on my first trip to Afghanistan in 1985 did the Soviet pilots who dropped bombs on the villages I had just left or was on the way to, ever come close. That is bad luck for a war photographer, but good luck for everyone near me. My wife claims that definitely it was her special prayers that did it, and I believe her, though I did not have the cheek to ask her to not pray so hard, just once, so I could learn the truth about my luck. Last August I arrived at a firebase on the Pech River a day after it was mortared. I stayed with the men of Able Company of the 173rd Airborne Combat Brigade for ten days and nothing happened. The day after I left a SPIG 9 (recoilless rifle) round landed in the parking lot, not 20 feet away from two men. One was peppered with small bits of shrapnel, and the other went down on his knees and suffered a concussion, though he was otherwise untouched and remembered the entire event. The front tires of the two Humvees near them were shredded. I might have been photographing those men when that rocket landed. I moved between firebases and observation posts and I went with patrols looking for weapons in villages that had harbored the Taliban. Nothing happened. I went on a three day operation into a district where the company I was with had been hit every time they went in. The first time they lost two men. The last time was two weeks before their 15 month deployment ended and they were to rotate back to Italy. That was when they took me along. Nothing happened. After that, in their eyes, I became a good luck, anti-combat charm. They wanted me to stay until the end of their deployment, two weeks away. My luck went beyond my immediate vicinity. As we were returning from the operation in Watapur valley, a Kiowa (Little Bird) caught on fire and fell out of the sky in a field 500 ft. away from the convoy. The crash landing was hard enough to snap the boom and wreck the hub and the rotors and the skids, but the fire went out and the two pilots walked away unhurt. It was incredible any way you look at it, but some people began to think it was my mojo working, not the skill and luck of the pilots that saved them. The convoy stopped to protect the helicopter. We were in enemy territory, strung out on a narrow road through a hostile village waiting for a big bird, a Chinook, to lift the Little Bird out. For four hours we were sitting ducks. Nothing happened. Some of the men took up defensive positions above the road, the rest stayed in their Humvees, turning in their machine gun turrets or taking turns sleeping in the one vehicle in which no one has ever discovered a way be the least bit comfortable. Perhaps it was all meant to be. If I were a Muslim I could say Inshallah. But I could not mean it. It is my chosen fate, if you will, to take pictures of what is remarkable in an ordinary day, not Allah's. And an ordinary day of the soldiers in the foothills of the Hindu Kush, along one of the most dangerous borders in the world is not ordinary in any way. The Islamic terrorists keep coming into Kunar Province and the soldiers keep killing them. The patrols go out every day, every night. The soldiers spend hours getting ready for a mission. Then they come back, de-brief, and try to sleep, any way, anywhere they can. Then they pack up and do it again. War is hellish and ugly and there is no excuse for it, but the soldiers who fight wars do not start them, they only have to win them. Paradoxically, when they do it well it is a beautiful thing. Combat is where all the qualities of a successful personality are tested. Those who pass gain a wisdom that no other job has to offer, though all have to endure the damage, more or less. I listened to a soldier telling me about treating, under fire, a bleeding, dying comrade, desperately trying to find where the pool of blood was coming from, then having another man, also a close friend, already dead, drop on top of him. I felt insignificant in the presence of this very young man. These photographs are part of a larger book project whose working title is "War and Peace in Afghanistan". My intent is to show, not tell. I hope my photos speak for themselves. They are ordinary images whose only intent is to show you something extraordinary. As the Watapur operation was winding down on day two, the Afghan interpreters who were monitoring the Taliban's radio messages, called ICOM (a brand name) chatter, told me some of the things they had overheard. Early in the operation someone warned: "they are powerful". Later in the day, another voice said "We are hungry, can we make lunch now?" Finally, best of all, someone asked "We are tired, can we do jihad tomorrow?" Was I good luck to the men of Able Company? I don't think so, those guys made their own luck, the hard way, I just came along to enjoy the lift. |

|

|