Flying Close to the Sun

![]()

|

Flying Close to the Sun |

|

After crossing the Atlantic solo in a homemade plane, Versace's Andrea Tremolada would appear to have a death wish. SARAH RAPER LARENAUDIE tracks him down.

by Sarah Raper Larenaudie

photographs by Settimio Benedusi

|

This article appeared in the September 24, 2000 issue of the New York Times Magazine. |

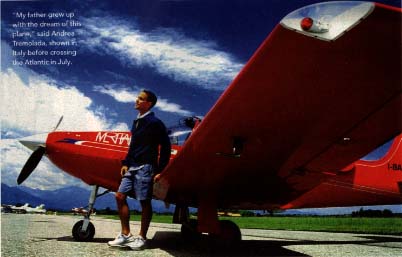

"My father grew up with the dream of this plane," said

Andrea

Tremolada, shown in Italy before corssing the Atlantic in July.

Five hours into crossing the Atlantic in his wooden, single-engine plane, Andrea Tremolada began to have serious doubts whether he'd live to see the coast of Brazil. The steady drizzle that had followed his red Falco F.8L from Sal Island, off the coast of Senegal, suddenly turned into a convulsive thunderstorm. In seconds, his 22-foot plane shot from 8,000 feet to 15,000 feet and slammed back down. "Those accelerations were breaking the plane," he said. "And the cockpit was full of water. I looked al my watch, and it was 11:23, and I said, 'This is the time I am going down.'"

Tremolada, the 34-year-old director of advertising for the Versace fashion house, had been warned by experts -- from the legendary 81-year-old Italian aeronautics engineer Stelio Frati, who designed the Falco, to the American entrepreneur who sold Tremolada the plans, to the mechanics at the country airfield in Biella, Italy, who had helped him adapt the craft for the trip -- that the flight would be his last. After all, before his trans-Atlantic jaunt, the most air time he'd logged in the craft was a mere 6-1/2-hour tune-up flight around Italy.

In the weeks before takeoff, Tremolada became obsessed with exorcising the plane of every potential kink, but he also seemed to revel in the danger. Leaping from the cockpit of the Falco one day at Biella, he slipped on a pair of white feather angel wings. "Instead of a parachute!" he yelled to friends at a nearby bar. In fact, there was no parachute, and otherwise the gear list was so miserly that it almost seemed cavalier: an onboard radio (out of range for most of the trip) and a screwdriver. His flight uniform and personal gear consisted of Nike beach sandals, a bathing suit, shorts, a T-shirt, a fishing hat, a CD player, worn copies of "The Little Prince," by Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, and "Long Distance Flying," the aviation writer Peter Garrison's 1981 account of crossing the ocean. And a toothbrush.

The whole package had a slightly self-destructive feeling to it. Does he have a death wish? "No, I don't have, but I like to go very close," Tremolada declared at a lunch with friends several days before he attempted the crossing. "I am very curious. We like this life very much, but we don't know what else is out there." Days before leaving, he typed a goodbye letter to family and friends, added handwritten notes to each copy and lefl them poking out of a drawer in his desk at Versace -- just in case.

Tremolada was a schoolboy when he decided to build a plane and fly it across the Atlantic. He grew up tagging along with his father, also an amateur pilot, on trips to small airfields around Milan, near where they lived. When he was 13, he and his father read that an American company had acquired the rights to the Falco the sleek stunt plane they admired most, and would begin selling kits to build it at home. Five years later, Tremolada used his first paychecks and all his childhood savings to purchase the plans, and the following summer the Tremoladas began building the Falco in their garage. Construction stretched 12 years. "My father grew up with the dream of this plane," said Tremolada, who called his trip "Two of Us" in memory of his mother, who died last year. "To finish the plane was my reason of life."

Flying a single-engine plane across the Atlantic is perhaps not as dramatic as it was in Lindbergh's day -- but then, you need the right plane. Frati designed the Falco back in 1955 to look fabulous and handle better than any other civilian aircraft, but he never intended it to go for more than four hours without refueling. With good weather and favorable winds, minimum flying time for the longer and more treacherous southern Atlantic crossing is 12 hours in a small plane. So Tremolada fit the Falco with three low-tech aluminum gas cans, which filled the seat and all available legroom on the passenger side of the plane. They carried 150 gallons of fuel, four times the recommended limit. The extra fuel threw off the plane's center of gravity and required a the pilot to take off with the tail dragging. After the cans broke apart in test flights last spring, Tremolada reinforced them with fiberglass goo. Still, he was sure a trans-Atlantic crossing was possible, he remembered watching the Italian pilot Contardo Giorgi prepare his Falco for the same trip back in 1977. Giorgi famously told his wife he was going out for an errand, then flew to the African coast and on to Brazil. The following year he attempted a second crossing but crashed and died on takeoff.

Early on July 3, Tremolada and his tanks staggered down the Sal Island runway and into the air, awkwardly but without incident. His itinerary closely followed the one that Giorgi had flown. Although he had planned to listen to music and read between his half-hourly log entries, the rain and clouds kept him busy at the controls. But the plane, which had undergone various repairs en route to Sal Island, was flying smoothly. He ate an apple, sipped from a bottle of water and relieved himself when necessary in a container, which he emptied from the window. The surprise thunderstorm provided the most harrowing two minutes of the trip, and emerging from the storm alive and still aloft was the most joyous moment of the trip. Tremolada said that he cried and celebrated with a prayer and several aerobatic rolls. When the weather turned threatening again, he dropped to just 200 feet above the water and hovered there for the last five hours of his trip. He was below the thunderclouds but had no margin for error.

| Days before leaving, he typed a goodbye letter to family and friends -- just in case. |

Finally, 12 hours 43 minutes after takeoff, Tremolada touched down on the eastern tip of Brazil in Recife and watched as local aviation authorities prepared to confiscate his plane. He says he was detained for hours by aviation authorities over a landing-fee dispute. Furious that the officials had spoiled his moment of glory, he blasted them in the local media. The Brazilian aviation authorities, through a Washington spokesman, denied there were any problems, but Tremolada has a copy of an order to confiscate the plane. He says authorities refused to allow him to change his flight plans to leave earlier than he had originally planned, and he began to worry that he would not be allowed to take off.

A week after his arrival, he was approved for takeoff and was in the cockpit when the authorities changed their mind. Tremolada will not discuss what happened next, but friends say he left without permission, and arranged through people he had met at the airfield to make a getaway in a rented plane via a network of private airfields maintained by gem smugglers and wealthy landowners. His Falco, too damaged by the storm to make the return trip, was dismantled and shipped back to Italy.

Back in Milan, Tremolada says he is busy planning another trans-Atlantic crossing -- "This time in a bigger plane, because I've been very lucky, I've risked so much and life is so important." But he's longing to re-experience the thrill of pushing himself to his limits. However, he's also feeling empty now that his long-held dream has been realized. "I think sometimes it was stupid. What I did is useless. Everything has already been done," he said. He added: "It was not a goal for aviation. It doesn't belong to anyone else but me."

|

|