Building a Falco,

Part 1

![]()

Building a Falco,

|

|

by Stephan Wilkinson

This article appeared in the April 1986 issue of Pilot magazine in England.

Unless I become unspeakably wealthy, it will forever remain my largest impulse purchase: $50,000 worth of wood, aluminum and avionics with which to create a Sequoia Falco F.8L, one of the most sophisticated homebuilt-airplane kits ever to be offered. And me, a first-time homebuilder.

I had never before imagined making my own airplane. A great deal of effort to reach a marginally useful goal, said I, accustomed to flying well-equipped production airplanes that were equal to any task to which I had the skill to put them. Homebuilts are amusingly limited designs built by people who couldn't afford proper airplanes, said I, forgetting that not everybody who flies can be an aviation-magazine editor or writer-in the one case being provided free with every variety of new airplane and in the other being able to tax-deduct flying as a business expense. Takes too much special skill and too many exotic tools, said I, ignoring the workshop with which I had built much of a house and all of a studio.

But I'm a kit junkie. Show me a raw block of spruce and I see firewood. A roll of naked 2024-T3 aluminum is tin waiting to become cans. But open a carton full of zip-locked whifflepads, cut-to-length muffler bearings, carefully tagged decompensator brackets, predrilled kanibbling pins and my hands begin to twitch. Insert Tab A in Slot B will be my epitaph.

Kits have been an affliction since childhood. Strombecker solid-pine B-25s as a little boy, balsa Guillow models as I grew older, Dynakit pre-amps and tuners in college, the six-foot-span R/C Stearman that still hangs at the top of a loop from my bedroom ceiling, garden carts, toolsheds, Windsor chairs, Shaker furniture... the smart marketer could charge me extra for a kit product that sells for less fully assembled.

So it was with the Falco. One glimpse of the million dollars worth of parts stacked on shelves and catalogued in bins in the Sequoia Aircraft warehouse in Richmond, Virginia, and my lips began to go dry. A look at the blueprints Sequoia President Alfred P. Scott so casually spread before me-just a taste of the 125-odd sheets and hundreds upon hundreds pages of detail drawings-and it all came flooding back. Stop me before I assemble again.

Too late. My Christmas gift from my wife in 1984 was permission to begin construction of one Falco. Either the cheapest or most expensive gift she'd ever give me.

The Challenge

The Falco has an undeserved reputation for being hideously complex-a project

only the most experienced homebuilder should tackle. That would indeed be

true of a totally plans-built Falco, for the airplane is an all-wood amalgram

of curves and tapers. You'd spend hours building a wing-rib jig, and it

would suffice for two ribs-one station on each wing. Next jig.

Ten thousand hours of skilled labor, craftmanship and machining should suffice to convert one tall Sitka spruce, a grove of Finnish birch and a pile of aluminum extrusions into a flying Falco totally faithful to Sequoia's detailed plans. Sequoia Aircraft, however, has designed a series of kits that turn the Falco into not homebuilding but home assembling. Ribs. Brackets. Grease nipples. Cut-to-length and color-coded wires. Formers, longerons, washers, pins, post lights, instruments. A completed assembled, laminated, glued and tapered main spar that is alone the price of a used car but worth it.

There are three varieties of kits that go into a Falco: wooden parts, metal and hardware components, and ancillary pieces such as the exhaust system, radio antennas and instruments. The wood kits are all made by a large, gentle, slow-talking Wisconsonian named Francis Dahlman, whose name will appear with mine on the airplane's data plate when it is complete. For me to say that I alone built the Falco would be to value the contribution of a craftsman as less worthy than the doggedness of an assembler.

The hardware kits are supplied by Sequoia itself, which has subcontractors produce finely machined brackets, hinges, cables and controls in cost-efficient batches of fifty or more; and accessories come from suppliers with whom Sequoia has struck deals. Every nut, bolt and piece of hardware is separated into hundreds upon hundreds of satisfyingly small, neatly labeled envelopes.

More important, the time to build an all-kits Falco is down to somewhere between a fifth and a tenth of what it would take to make one from scratch. Estimates vary: Sequoia claims an easy 1,500 hours, maybe 1,200 or less for a really well-organized builder with plenty of equipment and experience. Two thousand hours should cover even the most inept. The current record is a Falco built from kits in one month less than two years, accomplished by a wealthy father-son team with a well-stocked workshop amid the warmth of California.

But who cares? Perhaps the people who buy a book because it's a fast read-something that can be wolfed down during a single airline flight. But what do they know about the joy of actually reading, savoring structure and finely polished phrases? Perhaps the people who buy plastic homebuilts because it's said you can pour them out of a bottle and be airborne 400 hours later. But what do they know of the ruminative pleasure of sanding spruce to a cheeky smoothness, or glorifying in a glueline as thin and tight as a silk thread?

No, for me, the Falco would quickly become a novel that I'd finish reluctantly, a vacation from trivial concerns that I'd end with regret.

Or-no pun-would it?

Cutting Wood

Falco builders go to school on the tail section, assuming they get past

the stage of studying the fascinating plans trying to imagine how they could

ever possibly build anything so large and complex. The tail is a microcosm

of all the airframe construction, with spars to drill, hinges and brackets

to carefully align and mount, jigs to make, spruce to glue, sheets of thin

plywood to bend and clamp. It also costs little more than $2,000 for all

the necessary kits, which can fool you into thinking this $50,000 airplane

is going to be a bargain. (Admittedly, I'd also spent another $1,000 on

plans, small special tools, glue, jigging table and other items before settling

to work on the tail.)

The tail taught me that even cardboard-thin plywood doesn't bend against the external grain, no matter how long you soak it in the bathtub. That the choreography of gluing is a dance that moves quickly to an inevitable finale of thickening glue, sticky fingers and misplaced clamps. That ribs butt-glued against a spar break off with shocking ease while the assembly remains unskinned.

Sequoia's Alfred Scott, the man who refined this 1950s classic for the '80s, is nonetheless a conservative when it comes to glue. The recommended glue with which to build a Falco is resorcinol, a traditional water-resistant woodworking glue of tremendous strength and durability that requires perfect mixing, warm temperatures and finely matched surfaces. Second choice-my first-is something called Aerolite, a glue classic enough to have been used by de Havilland in Mosquitos and considerably less demanding of technique. Aerolite is a fine white powder that could easily be used to cut cocaine, thus gluing shut the nostrils of an entire generation of addicts. It is mixed with water to make a stable paste that quickly hardens in the presence of a weak formic acid mixture: the glop goes on one surface, the acid is brushed on the other, and they are quickly mated and clamped or stapled.

The least desirable glue, according to Scott, is the epoxy that other homebuilders have come to depend upon. Powerful and user-friendly as they are at normal temperatures, epoxies have the strength of library paste when it gets hot. Use epoxy and you've no choice but to paint your airplane white lest the sun soften the glue, warns Scott, and what good is a Falco painted the same color as all the other flying appliances in U.S. skies? On the other hand, Scott admits that no matter what the shear-strength tests say, there has never been an epoxy failure in a homebuilt.

The traditional way to test aircraft glue-the purists do it every time they mix a new patch-is to glue together three small blocks of maple, the center one staggered about half an inch higher than the two that sandwich it. When the glue has set, you perch the assembly on a solid surface and pound the protruding block with a sledge. The result should be a break in the wood rather than the glue, the theory being that any glue stronger than maple will certainly suffice for soft spruce.

Gluing together a wooden airplane, which seems at first a simple process-mix and apply, clamp and dry-is actually fraught with opportunity for error. Assuming a metal structure is properly engineered in the first place, the rivets that hold it together generally make apparent their faults if misapplied. They rattle or move if loose, look squashed or asymmetrical if misplaced. But short of a joint that falls apart in your hands, the only way you can prove the integrity of a glued wood structure is by testing it to something approaching destruction to conclusively prove its integrity, since the bond can cover a considerable range of effectiveness depending on technique, temperature and numerous other factors. Sticking together three cigarette-pack-sized blocks of hardwood is one thing; wrestling a cardtable-size sheet of skinning plywood into submission is another.

The pieces are bonded, that's obvious; there's the thin line of glue between them, here's some hardened exudate, the structure can be handled without collapsing... but was the clamping pressure hard enough? Too hard, perhaps, squeezing the glue from between the pieces? Did you get the assembly clamped quickly enough, or had the glue already set? Did the wood stay sufficiently wet with the formic acid catalyst during your fumblings, or were some forever-hidden areas too dry to spark hardening of the glue?

And if that isn't worrisome enough, much of a Falco's airy internal structure is delicate no matter how well glued until given the strength of its skin. Before learning this, I snapped ribs off elevator and stablizer spars with terrifying abandon while sanding the structure, and even my small daughter was smart enough to say I'd never get her up in something held together with glue.

One of the delights of building a Falco, however, is the airplane's clubbish, intensely personal builder-support network. It consists of virtually every Falco-builder in the world plus Alfred Scott, in Richmond, Virginia, who is instantly accessible any hour of the day or evening except for the times when his secretary says, "He's on the telephone shouting at Chile, Mr. Wilkinson. The Chilean Air Force is just about to fly their Falco." (Scott's illustrated and extensive quarterly 'builder letter' ranks as one of the better aviation magazines in the U.S.).

Scott soothed my fears and explained the massive strength of each box-section or monocoque component of the airplane and how vastly it multiplied the strength of the tiny area of glue holding the end grain of a single rib to a spar. John Oliver, a builder who knew his chemistry from years at Du Pont, sent a letter with gluing advice. Somebody else mailed a Xerox of the detailed Aerolite-use instructions I'd been unable to acquire through Ciba-Geigy, whose marketing department seemed unaware that they held the patent on a World War II glue.

Brook (6) holds a fuselage frame, signed by Steve, Susan and Brook

I forged ahead with somewhat more confidence and soon had the tail finished. By mid-summer, the empennage sat temporarily assembled on a pair of sawhorses, and I was able to demonstrate The Miracle of Trim-Tab Movement by pushing and pulling on the end of a long Bowden cable that would eventually lead to the cockpit. My Falco investment stood at $4,256.62-parts, plans, books, cable and wiring to electrify the barn... everything. (Like every homebuilder in the world, I'd assidously logged my building time daily for about a month, then gave it up as a bore. I continued to count the dollars, however.)

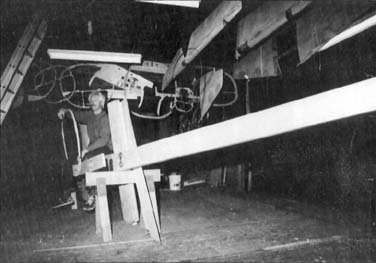

Spar Session

By taking a perverse pride in doing things alone the hard way that could

by done in a trice by two working together, I assigned myself the job of

fetching the main spar when the call finally came that it had arrived from

Dahlman's shop in Wisconsin. It is one piece, of course, tapering to fine

points thirteen feet in each direction from a central box the size of a

railroad tie.

Other homebuilders have bandsaws and winches, engine stands and airplane jacks. I have none of them, but I do have a dead-serious 1967 Chevrolet four-wheel-drive pickup that makes today's little trucks look as though they should be wearing lingerie. With a beefy pipe rack erected atop the bed, the truck was ready for the transfer from shipping-company warehouse to barn, and after some serious prying, lugging, lifting and sliding, the 400-pound dihedraled box that held not only the main spar but secondary spars and all the wing ribs was home. It cost me an endless, 20-mph trip during which I was entirely conscious of the $4,475 value of the box cantilevered up over the cab and well out ahead of the front bumper.

Worse, however, was submitting the spar to a drill press to bore the boltholes for the main landing-gear trunnions. Faultless Francis Dahlman's placement of the two arm-sized holes through which the gear-mount beams would pivot were inexplicably off by about five millimeters, it seemed. I measured, remeasured, checked again, started over. Still off. Locating the main-gear fixtures is a relatively complex process of establishing a dead-centerline, laying out horizontal references, establishing angles and swinging arcs. Opportunities for error-mine as well as Dahlman's-abounded.

The hell with it. Let's drill. We can always shorten one wingtip. That's the nice thing about wood, isn't it? Isn't it?

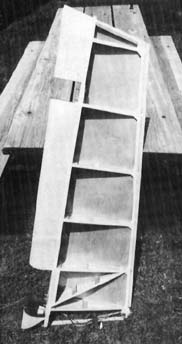

The Right Stuff

As winter fell upon the Hudson River Valley, I shifted the Falco shop from

unheated barn to cluttered cellar and built the Falco's ailerons and flaps.

Some say they are the most difficult part of the airplane to make properly,

in large part because as the stations progress outward along the aileron/flap

spar, each rib is sanded and set against it at a microscopically greater

angle, to create a trailing edge that gently washes upward some thirteen

millimeters between flap root and aileron tip.

Sequoia's Scott persists in giving blueprint measurements in cases such as this in tenths of a millimeter. Some Falco builders construct complex jigs and clamping devices to achieve and maintain such exacting standards. I try, but clamping and gluing large pieces is like wrestling with a walrus: they are heavy and smooth, and it's difficult to get a grip on them. I content myself with knowing that the shape of the airplane will change by gross fractions of an inch as it absorbs heat and moisture on a humid summer day.

It is both remarkable and infuriating that Scott, who can see the entire construction of a Falco in his mind's eye, has himself never built one. He sometimes recommends assembly procedures that for me, at least, are interesting in principle but utterly impractical. To properly bend and clamp down the uncooperative leading-edge skin of a flap or aileron while the unit is held securely in the recommended jig, for example, requires either drilling large holes through the workbench or using specially constructed aluminum band clamps. Other builders can do it. I am too impatient.

Ten feet long (each wing's control surfaces are built as a unit and sawn apart only after skinning), the flap/aileron units were the largest pieces the cellar could handle. The frequent transfer of delicate spruce structure from cellar jigging table around the oil burner and up the narrow stairs to the warm kitchen for good glue-curing became an infuriating journey-clamps clanking against obstructions, the paper-thin trailing-edge strip becoming increasingly dented-and I needed a more manageable component to carry me through the rest of the winter.

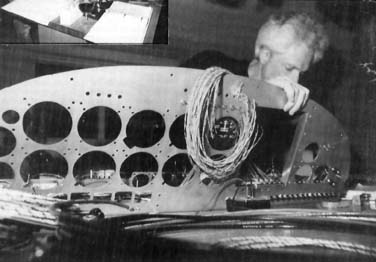

It would be the electrical system and instrument panel, a $5,700 leap of commitment. No longer could I convert the airplane into firewood if I became discouraged.

Wood is nice, but hardware-parts-is better. Wood is sticks, furniture. Hardware is instruments and bellcranks, pulleys and panels and lots of other airplane-looking things. When visitors see a carefully wrought aileron or disembodied tailfin, they're amused. "Oh, you're just starting," they say, which is almost as condescending as that other inevitable comment, "Is it an ultralight?" But let them see an instrument panel leaning casually against a living room wall, and they know you're a big-time operator. (As soon as my panel blank arrived from Sequoia, in fact, I stuck an old Comanche manifold-pressure gauge into it, so there'd be no mistake.)

The Falco's electrical system is a relatively complex one. Nothing unconventional, but the wiring harness is designed to run a complete IFR avionics kit, an excessive variety of indicator lights and upscale toys such as a combined four-cylinder CHT/EGT, an electronic outside air temperature indicator and an alternator fault analyzer. (Mine, however, will have a steam-powered OAT, and the alternator will have to be content with being either broke or not broke.) The harness consists of hundreds of tiny wires, many of them passing through three large multiple-pin-and-socket receptacles on the back of the instrument panel, disconnection of which supposedly means the instrument panel can be removed as a unit.

The electrical kit arrived in a coffin-size cardboard box with its own builder's manual and set of blueprints. It included everything from finger-thick battery cable to grain-of-wheat lightbulbs, transistors to microswitches. And miles of slick, expensive, Teflon-insulated wire, all of it cut roughly to length and color-coded. Yellow wires with red, gray and violet striping. Yellow wires with red, blue and violet striping. With brown, gray and violet striping. With every combination, it seemed, of nine colors and half a dozen thicknesses.

I had soon created a trio of basic harnesses and carted the heaviest of them off to a nearby truck garage so they could crimp terminals to the main power-circuit wires. (It's often a help to be able to say, "It's for a small Italian aerobatic airplane that I'm building." Specialized merchants who might otherwise ignore you drop everything to help, unless they are sophisticated about product-liability implications, in which case they throw you out of their shop. The ideal tire for a Falco's mainwheels is made by Goodyear for boat trailers, for example. "Do not say that you want it for an aircraft, or you will never get a tire," the Falco builder's manual warns.)

One of the pleasures-and dangers-of commitment to a project of such magnitude as an entire airplane is that as outrageous expenditures become necessary, moderate expenses become insignificant. The $80 tool is bought as though it were a K-Mart screwdriver. Furniture-quality wood is converted to sawdust with abandon. And I barely winced when the tiny white amperage numerals on my instrument panel's fifteen push-to-reset circuit breakers cost $1 a piece. Because of the panel's design, the breakers must be positioned upside-down-a condition of which the breakers are entirely unaware, but it does result in their power-rating numerals standing on their heads. The builder's manual advises sanding the numerals off and restoring them right-side-up with tiny press-type transfers: $10 a sheet at a Manhattan art supply store, plus $5 for a can of spray fixative.

As the ganglia grew behind the instrument panel and the warehousing of semi-finished airframe components spread from barn to attic to dining room, I for the first time imagined flying the mechanism that I was creating. That violated by own overly cool approach to the project. "Oh, I don't care about flying the thing," I had been telling people, "It's the building that matters; I've already got a perfectly good airplane to fly."

It also formented dark thoughts, and occasionally I had to switch off mental images of the very first kit-built Falco every to be completed. It was a stunning, glass-smooth little airplane completed less than two years ago by a middle-aged Minnesota executive who only months later died amid its bloody splinters in Gainesville, Florida, apparently having run out of fuel during a night-time instrument approach. Automobiles and airplanes carry with them a certain cargo of danger. To walk into a showroom and buy a vehicle can certainly turn out to have been a momentary deal with the devil, but to have spent years lovingly assembling the instrument of one's mortality would be a dreadful indignity.

No Turning Back

What more pleasant lessons have I learned from all this? That there's no

turning back now, for one thing. I'm $19,510.81 into this thing, and the

tail can no longer be turned into a coffee table. Ownership of a Whelan

strobe-light system that I blithely bought for as much as our entire stereo

cost means the trellis of spruce to carry it must eventually be completed.

Possession of $9,150.59 worth of Dahlman-crafted spruce and Wicks Aircraft

birch plywood sheets would supply our two woodstoves for... oh, maybe two

days. Soon there will be an engine sitting in a corner of the barn to hurry

me along as well.

I think I've also discovered the two ingredients necessary to make building an airplane a pleasure. One is that unless you desperately need an excuse to get out of the house, build it at home, no matter what sacrifices that requires. It allows you the option of spending fifteen minutes gluing a couple of ribs or dawn to dusk wrestling with a Medusa's-head of avionics wiring. It also provides easy access to all those things that can suddenly become a desperate necessity yet exist in few hangars: a kitchen knife, a roll of waxed paper, two dining room chairs, a stray length of 2x4, a plastic-coated playing card just the right thickness for a shim... for the casual homebuilder, tools are where you find them.

The other necessity is an open-ended schedule. You need an airplane to fly? Go buy or rent one. It'll probably be cheaper in the end anyway. When people ask me when I will finish the Falco, I tell them that my daughter has been penciled in to make the first flight, and since she's six now, that gives me a good ten years.

And finally, I've learned I can still get a rise out of my wife. All I need to do is tell her that I'm thinking of building a Swearingen SX-300 next.