Building a Falco,

Part 4

![]()

Building a Falco,

|

|

by Stephan Wilkinson

This article appeared in the September 1991 issue of Pilot magazine in England.

I finished the Falco without knowing it.

You'd think it would be a major moment-a ceremonial last levering of the torque wrench, a final dab of touch-up paint, an ultimate electrical connection made good-but it doesn't work that way. Completion sneaks up, then sits quietly in a corner of the workshop waiting for you to notice.

Of course the Falco wasn't finished finished. It probably never will be, for there's always more to do on a project airplane: speed to seek, mistakes to correct, glitches to fix, the difficult lessons of daily operation converted to hardware. But one unusually balmy October afternoon, hurrying to get some jobs done before a writing assignment took me away from my barn and its rude shop for a week, I hooked paint pot to compressor and casually sprayed onto the airframe two coats of fast-drying primer the color of a baby's diaper deposit. I knew this might be the last convenient day warm enough to paint before the onset of winter.

The airplane was already covered with numerous coats of Featherfill-a talc-rich automotive sanding primer that can be smoothed to a glassy surface as easily as sanding soft balsa. But Featherfill is hygroscopic: it attracts and absorbs humidity. Woe betide the wooden airplane left in a damp, snowy barn with an unpainted coating of Featherfill, for it rotteth therefrom.

The Featherfill-and the attendant "microfiller" that is troweled on to correct grosser mistakes before the sanding primer is applied-had another unfortunate quality: It encouraged endless fiddling and sanding, smoothing and perfecting. Enough was never enough. Never could I get the wing perfectly smooth, the fuselage silky. There was always another minute dip or hollow in the airplane's skin.

The khaki paint put an end to that. I was finished. I could no longer touch the airplane with sandpaper or file. What I saw was what I got. Oh, someday I'd finish-paint the damn thing, but only after I'd flown the Falco enough to know it was debugged, reliable, complete. Some argue that a homebuilt must be painted before it is ever flown, else the fluids and exhalations of normal operation will have sullied the airplane's skin. But since well-used airplanes are routinely repainted after years of operation, that seems a silly argument. Besides, most manufacturers production flight-test their airplanes before painting them.

Oddly, I was in no hurry to get the airplane to an airport, to get the Falco flying. It became winter in due course, so I manufactured myself some more jobs. Making gear doors, for one. Nobody has successfully gotten a Sequoia Falco to operate routinely with its full complement of optional gear doors, but I built them all just in case I'd be the first.

The fully optioned Falco has seven gear doors: a pair of typical main-gear doors that close inward with the landing-gear legs to cover them; a pair of big wheel-well doors hinged near the aircraft's centerline to cover the rest of the main gear-wheels and tires; two narrow doors that clamshell to cover the nosewheel leg and tire; and a final forward-facing door attached to the upper part of the nosegear and closing in concert with it.

Levering all seven doors to seal the Falco's belly seems to overwhelm the airplane's electric landing-gear motor. In fact, the landing gear is one of the Falco's touchiest systems. Early homebuilt Falcos had gear-retraction problems apparently due to voltage drop over the distance from relays to motor, but even after modifications to the wiring, Falco owners continue to gripe about the demands on the motor's gearing, particularly when all the doors plus the landing gear need to be dragged through the air during the retraction cycle. Some Falco owners make it standard operating procedure to assist gear retraction with a final turn on the manual emergency crank between the seats, for the motor sometimes can't snug all the wheels and doors into place unaided. Or if it can, the effort pops its circuit breaker.

No matter. Every homebuilt airplane has foibles, and anybody who thinks they're getting a dead-reliable beater needs to go buy a 172 or a Cherokee 140 and suffer the consequences of butt-ugly flying.

The Falco's front fuel tank has turned out to be another problem spot, for several Falcos-one of them Neville Langrick's, in England-have sprung hairline-crack leaks in the front tank. It is a saddle-tank affair directly in front of the instrument panel-an archaic design from the days of Spitfires and Cubs, a piece of crash-unworthiness that no certificating body would today allow.

I told Alfred Scott of Sequoia, who markets the Falco plans and kits, that only the weekend before, an acquaintance of mine had been incinerated on takeoff in his Ercoupe when a long-standing leak in his airplane's similar saddle tank erupted in a fireball. They had yet to identify what remained of my friend's unfortunate passenger. "Did you have to tell me that?" Scott moaned after a long pause.

He set forth with monomaniacal concentration to find a fix for the cracking tanks-typical of his obsession with having the Sequoia version of the Falco as fully engineered and proven as any certificated airplane. It turns out there is an old CAR Part 3 FAA certification hurdle called the slosh-and-vibration test. It requires a motor-driven test stand that harshly vibrates a partially filled fuel tank at a frequency equivalent to cruise rpm while concurrently flopping the tank through the equivalent of 15-degree wing-rocking to each side. Scott builds a complete slosh-and-vibration rig. The Falco front tank cracks after four of the specified 25 hours. (When the test was performed by Mooney on one of their wing tanks some years ago, the first tank blew apart three minutes into the test!)

After three months of modifying, stiffening, rewelding and strengthening, Scott creates a fuel tank that passes the slosh-and-vibration test. The owner of the tank refuses to take it back, afraid that perhaps it has been torture-tested beyond reason, so I swap him my unused, unmodified front tank and happily put the weld-dotted, brace-laced Godzilla tank into 747SW.

Jonas Dovydenas, a New England Falco builder and friend, has bested me. An engraved card arrives in the mail, inviting us to the debut of his airplane on the lawn of the spectacular Dovydenas manse in the Berkshire Mountains of Massachusetts. My wife steals some of Jonas's thunder by casually riding her racing bicycle-a vehicle she loves as much as I do the Falco-the 100 miles from our house to the party, but I go by car. ("You know the one thing nobody forgot?" Jonas later admits. "Not the airplane but 'that woman who rode her bicycle.'")

Perhaps 200 people mill about the temporarily assembled, primered Dovydenas airplane as valets park cars amid the grove of enormous pines in front of the house. Caterers hoist trays and waiters dispense champagne and cocktails. Three of us are Falco builders, several more are local pilots, but the vast majority are neighbors and friends. Jonas is a photographer of considerable repute, so the crowd is eclectic.

I listen as one man tells his wife that the airplane will go 300 mph and another explained that the machine must be totally disassembled each year for an annual inspection. Dovydenas later admitted to being stunned by the number of otherwise intelligent guests who assumed he would do the first flight from the lawn, an area of perhaps 200 by 75 feet.

There are worse things than watching the airplane you've spent six years and $80,000 to build being moved on a bouncing trailer from a remote barn, across a rocky lawn bisected by a brook, down a steep driveway, along a one-lane country road, to the nearest highway and 20 miles to the airport amid Saturday-afternoon traffic. The only ones I can think of, though, bring to mind old photographs of a country church being hauled down a road on a 64-wheel tractor-trailer while the advance crew dismantles traffic lights and powerlines. Or of the little guy with the sledgehammer in his hands who's about to knock out the last wedge that will allow the entire frigate to either roll over on him or slide sideways into Penobscot Bay.

The moving crew began to gather at nine o'clock on a Saturday morning in April-friends, friends of friends, friends' girlfriends, people I'd never even seen before. Among the first to arrive was George, a sinewy, ruddy-faced local pilot in a USN cap who quickly took charge. Turned out he was a rigger, who made his living manipulating and moving huge objects. "George sees steel, his nipples get hard," explained his friend Tony.

In minutes, George had the Falco out of the barn despite six years of theorization by visitors and onlookers that the airplane would never fit through the door. Hey, this is going to be easy, I thought. The crowd had grown, about evenly divided now between experts and drones. The experts gave orders. The drones drank coffee. But no matter what they did, the airplane on its borrowed trailer wouldn't fit past the tree outside our kitchen windows.

"Be my guest," said George with exasperation as Jim, a mountain man who handles a chainsaw with aplomb, countermanded the rigger's plan on how to chop the handsomest-and biggest-limb off the tree without having it fall on the Falco.

Six-foot six-inch Gary, the photographer, did no lifting or toting. "I'm a prince," he said only half-kiddingly. "I usually work with an assistant, and I'm all alone on this job." Gary dashed hither and thither taking pictures, occasionally backing off a porch, plunging up to his ankle into the brook or stepping on his camera bag like a plumber putting his foot in a bucket. "Steve! Stand here and talk to Jim! Make believe you're talking about taking that other tree down." Aw, no, not another one.

The Falco's tail and fuselage afterbody was proving to be the most irksome component to move. Though light enough for two people to carry-and equally delicate-it was shaped like a child's huge jack missing an arm or two.

Jim had become a flurry of activity, a househusband released for the day from tending to his two little boys. "Lesley said I could even take the Aeronca and go away for the weekend if I wanted," he admitted. "Got any tires? Old tires? How about some more of that foam rubber that's in the barn? Blankets? We need blankets." Four drones trotted past, bearing the delicate tail, and it was tossed-oy, I can't bear it-up into a borrowed truck, where Jim bedded it down and strapped it like a gorilla being delivered to Clyde Beatty.

Listen, I'll go rake up some grass clippings. I'd rather not watch. Lunch... yeah, that's the ticket, I'll make lunch. With my wife, a take-no-prisoners shopper, away for the week on a business trip, I'd already indulged in all the supermarket excesses she loathes: The best ground sirloin for the hamburgers, and nine pounds rather than the three I'll need. Six-packs of imported beers I'd never even heard of. And finally, boxes of yuppie-priced ice-cream bars for dessert. By the time the hamburgers were on the grill, the crew had everything on the trailer and ready for the towtruck, due to arrive in two hours. By the time the ice-cream bars appeared, they were offering to move the entire barn next weekend if I'd promise to make lunch again.

The towtruck-a homebuilder friend's huge van-finally showed up, and the parade began. The local police stopped traffic long enough for our caravan to pull onto Route 9W-the highway that will forever represent for me the answer to the musician's question, "Do you spell your name with a V, Mr. Wagner?"-and we were on our way to Dutchess County Airport: two trucks, a trailer, six cars with flashing lights, one photographer and a pickup truck I'd never even seen before.

Unfortunately, reaching the airport required crossing the Hudson River on an Interstate-highway toll bridge. By several illegal inches, the Falco was a wide load. Would we be caught? We could hardly hope to slip through unnoticed, but George's friend Tony turned out to be a recently retired New York State Trooper. "Leave it to me," he said. "They won't bother ya." Tony negotiated briefly at the tollgate, and we magically became a narrow load.

Drivers in other cars pointed, jabbered and swiveled their heads as they passed, the Falco's bubble canopy and military-brown primer paint perhaps making it look like some new stealth fighter. But even more interesting were the few who drove by without a glance, as though they saw airplanes being towed along highways daily. Worst of all, however, was the rusty, listing Pontiac that veered into the convoy right behind the trailer, intent on getting as close a look as possible.

Was it possible to transport such a delicate mass 20-odd miles without a disaster, without even a ding? Slowly I realized that the half-ton of wood and metal I'd sheltered so carefully for six years had better not be all that delicate. For it was not only going to the airport but was beginning real life. A life in which it would be rained upon, in which it might spend some days half-buried in airport snow, in which the harsh summer sun would cook a structure that had never before felt its glow. It would even fly-there's a thought-while the pounding of its big four-cylinder Lycoming racked carefully bonded glue joints and vibrated every compulsively torqued fitting, while the Gs of aerobatics and bad landings flexed and bent an airframe that never was meant to sit in a silent barn in the first place. Mud would splash its carefully painted landing gear and oil would streak its smooth belly.

It took about ten minutes to undo what had consumed an entire morning of madness to create. The Falco came off the trailer and rolled onto the ramp like a boxer bouncing into the ring. Experimental Seven-Four-Seven Sierra Whiskey was finally home.

Home is a hangar-a piece of real estate as rare, around New York City, as a cheap Manhattan penthouse, a bad pizza or an empty highway. Yet it is my good fortune to find not one but three hangars.

The local EAA chapter has its own hangar at a nearby small airport, but their bylaws prevent my using it until I've been a member for at least a year. Fair enough, though I later learn that several chapter activists are miffed that they've therefore lost the opportunity to have such an exciting homebuilt as a tenant.

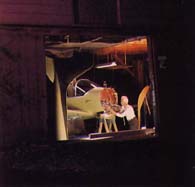

Dutchess County Airport is far friendlier. A mechanic I've never even met provides free hangar space for the two weeks it takes to reassemble the airplane. Then Daniel Helegoin and his wife Montaine Mallet, U.S. CAP distributors and teammates in the horrifying low-altitude aerobatics act The French Connection, volunteer their six-plane hangar and shop for the Falco while they're away for the summer air-show season. Their hangar probably holds more wood-and-glue aircraft knowledge than any structure in the country, and while I work on the Falco, an elderly Frenchman posted from the CAP factory chisels bits and smears resorcinol on the bellies of half a dozen disassembled CAP-10s subject to some arcane factory bulletin.

But best of all, the airport's young avionics technician, who helps me fix the inevitable wiring mistakes in the Falco's panel, chooses to permanently sublease me his private tee hangar, since he now has a newly built shop in which to park his Mooney 231.

Furnishing my little cinderblock space takes on all the secret pleasures of a college student's first apartment. Let's see: I'll set up a workbench here, some shelves over there, put down some carpeting scraps to keep the wingwalks clean, gotta get a portable radio to play some tunes, maybe a little refrigerator... I could buy an air compressor, a small electric winch to pull the airplane in, an engine preheater for the winter months... where will it end?

Depending on one's domicile, an FAA inspection of a homebuilt is to either be anticipated or feared. Not long ago, the FAA had to inspect a homebuilt before every permanent closure of a major component. Today, only one inspection is required: upon completion of the airplane, when it is in every way ready to be flown. Many inspectors have no knowledge of-or interest in-craftsmanship or lightplane construction techniques, and particularly in the shadow of the New York TCA one is assured of dealing with inspectors who spend most of their time negotiating toilet modifications with airlines or approving Donald Trump's helicopters for in-flight blackjack.

I prepared to climb Mount Bureaucracy by getting all the advice I could from local EAAers, who confirmed that the Teterboro FAA office was placard-crazed-that an airplane could be glued together with library paste and would be passed so long as every switch, knob, handle, gauge and container was accompanied by text. Montaine Mallet further advised that the careful candidate should leave just one "fault" for the inspector to find, else the FAA representative will implode from frustration.

My minnow was the canopy handle, and the FAA happily took the bait. "You'll need to placard that," the young inspector said-the Falco happened to be one of his first assignments-and demanded that an explanation be placed in full view of the occupants explaining how to extricate themselves from the airplane in case of terminal befuddlement. Since the Falco's hook-and-handle canopy closure is somewhat less complicated than a doorknob, we agreed on the legend, "Handle forward to open, aft to close."

Done and done. The Falco is legal. Let's fly the sucker.

Something like 10 percent of all the fatalities suffered in homebuilt aircraft occur on the first flight, thanks to the combination of uncurrent pilot (he or she has almost certainly been building rather than flying), unknown handling qualities (it's difficult for a homebuilder to get a checkout in a similar airplane, though several Falco owners had offered me theirs), and the potential for small anomalies to create a big emergency. A not-untypical scenario might be a malfunctioning airspeed indicator, a leaky oil line, a miswired comm radio that quits working plus landing gear that jams the first time you retract it under air loads. More than one harried homebuilder has spun in under such a burden.

Not me. My friend Mark Reichin, the best lightplane pilot I know, will first-flight the Falco. Mark flies almost daily and has owned everything from a Skylane to a 310. A local EAAer who has come to videotape the first flight for the next chapter meeting tells me that as far as he's concerned, what I'm doing is akin to "chasin' some broad for six years and then lettin' somebody else fuck her," but I'm fond enough of Mark that perhaps I'd give him that privilege as well.

My confidence is well-placed. Reichin makes a handful of high-speed taxi runs down Dutchess County's 5,000-foot main runway, gets good air on his penultimate run and floats back out of ground effect to a soft touchdown. Then, after a nervous pause for one more runup, Reichin goes for broke. The Falco climbs away, gear down as planned. The wings twitch and rock several times as Mark meets Frati handling for the first time, and my airplane fades to a speck.

Was it incomprehensibly thrilling to see it finally fly? Or was I terrified that its wings would clap hands on climbout, the unspeakable arrogance of my ineptitude finally revealed? Neither one, really, for my own several high-speed taxi runs had already made it obvious that 747SW would fly just fine: at 50 knots (which comes up at about half-throttle in a 180-hp Falco), the wings were light, the wheels weightless, the controls all sleekly effective. And to worry about structural failure in the framework of a Falco is akin to treading lightly on the Brooklyn Bridge for fear the cables might snap.

So I watched unemotionally as the little airplane buzzed around high above the airport, too far away to see that Mark was cycling the gear, running the flaps and making other checks, and soon it was over. One low pass down the runway, the Falco making a distinctive, dopplered, Spitfire-like whistle as it streamed past, and then I was back in my hangar with the sweaty little racehorse, Reichin and the EAA videotaper and several other friends gone their separate ways.

I wasted as much time as I could uncowling and recowling the airplane, checking every engine connection, cleaning and tightening tiny leaks here and there, inspecting yet again every control-surface nut and cotter pin. But the truth was that I had to fly it too, and oddly, I was putting off the moment-perhaps for fear that I'd be disappointed, that the Falco would indeed turn out to be just another airplane.

Silly boy. There is no thrill like flying for the first time an airplane you've built, especially if it's a Falco, and it took a single lap of the pattern to prove it to me. No American-trained lightplane pilot can possibly be prepared for the sensation of sitting in a fishbowl that extends unbroken virtually from one's beltline up, holding controls overpowered by anything more than the pressure of a finger, in an airplane that could find plenty of shade under either wing of a Skylane. It's like riding atop a large radio-controlled model.

Yet at that lightly loaded moment, 747SW's power-to-weight ratio was eight pounds per horsepower-identical to that of a P-51H Mustang at gross. It was almost impossible to apply full power fast enough to get the throttle advanced before liftoff, else the torque overwhelmed the nosewheel's ability to track straight. I found myself climbing out at 2,000 fpm at what seemed a 45-degree angle, and then squaring off the pattern with near-aerobatic banks. Only maturity kept me from the ridiculous singing and whooping I remember performing 25 years ago during my first solo.

Six years and $74,000 ago, when I began building the Falco, my wife presented me with a formally worded "certificate" authorizing the project, which would inevitably cost us an amount of money and effort perhaps somewhat beyond our means. "First-ride privileges are reserved by the undersigned," the document closed.

Several days ago, in happy disregard of all FAA regulations prohibiting the carriage of passengers in a provisonally certified homebuilt still under test, Susan claimed those first-ride privileges. She too is a pilot, both single- and multi-engine rated, though an unenthusiastic one who flew out of a sense of duty and hasn't touched a set of controls in over 10 years. "You know," she said after we landed, "I think I'll take some dual in this and start to fly again. That was fun." Thank you, Stelio Frati. Thank you, Alfred Scott.