The Awe-Ja-Magic

Fly-In Pancake Breakfast

![]()

The Awe-Ja-Magic

|

|

All it's missing is a fly-through window.

by Stephan Wilkinson

This article appeared in the February/March 1995 issue of the Air & Space. |

In the valley below, fog rose from Lake Seneca while the sun climbed quickly into the chilly September sky. I was shivering on my folding bicycle, pedaling from a Dundee, New York bed-and-breakfast to a tiny Finger Lakes grass strip nearby, where my little Falco-the airplane I had built in my barn and was finally putting to good use-had slept overnight. At 6:30 on a Labor Day morning, nobody was on the road, save one teenager who wailed past in a ratty black Camaro, foot to the floormat, the engine sucking air like a wild thing. The driver knew he had nothing to fear: there wasn't a state trooper between Rochester and Ithaca who'd had his first glazed doughnut yet.

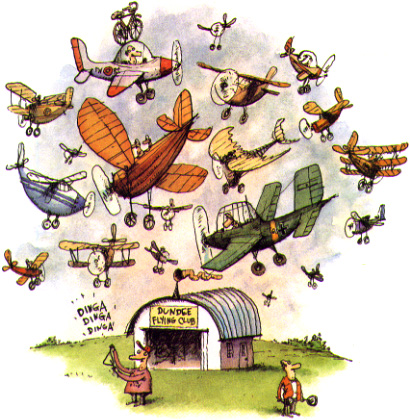

At the airstrip, however, things were a-bustle, for this was the morning of the annual Dundee Flying Club Labor Day Fly-In Breakfast, an event as monumental to this town of 1,500 as the Rose Bowl parade is to Pasadena. On the dew-soaked runway stood several men in orange vests, signal paddles in hand, ears cocked for the lazy hum of a distant airplane. "Here comes a customer," said one as a bright yellow Piper Pacer muttered into the pattern. By 7:30 the flow had begun-a steady stream of pilots who, for lack of anything better to do, had flown dozens and even hundreds of miles to eat pancakes with their cohorts. Not having the stamina to roust myself at 4:30 to arrive by air at 7:00, I'd flown in the afternoon before, transferring from Falco to baggage compartment two-wheeler.

The Experimental Aircraft Association, by far the world's largest organization of sport pilots, estimates that 10 to 20 major EAA-sanctioned fly-in breakfasts are held in the country every weekend between early April and the end of October, with countless more held by unaffiliated local groups such as the Dundee Flying Club. Fly-in breakfasts are just one manifestation of the American lightplane pilot's seemingly constant quest for food-a quest so unremitting, in fact, that it is an effective inflation index: what in the 1930s was called "the 50-cent hamburger" had by the 1960s become the $20 burger and is today $100 on a bun. It is the greasy patty served at any airport cafe somewhere over the horizon, half an hour's flight-and the expense it entails-away. And this despite the fact that some of the vilest, plainest, unrepentantly unhealthiest food in the United States is served at small-airport cafes. They are the last bastion of Route 66 home cooking. In fact, one explanation for the popularity of fly-in breakfasts may well be that the lunches at airport restaurants in the early days of general aviation were so bad that pilots generally made their cafe jaunts in search of breakfasts, which were harder to ruin.

Al Stivers, one of the organizers of the Dundee affair, thinks that fly-in breakfasts grew in popularity "because there were way too many church dinners already, and pilots were looking for something else to do." Stivers ought to know, since he's an Episcopal priest.

Of course, there are other reasons for the popularity of fly-in breakfasts. Many pilots were-and still are-farmers, accustomed to getting their days under way early. If they wanted a little weekend time to play with their airplanes, it would have to be first thing in the morning. Indeed, outposts of the Flying Farmers, a national club of aviating agrarians, have been hosting fly-in breakfasts since the 1940s. "I went to my first one in 1952, in Fairview, Oklahoma," says longtime Flying Farmer member Arlene Babb. "Why breakfasts? Well, breakfast is a cheaper meal to prepare, and if pilots have to come a long way to the breakfast, that gives them the rest of the day to get back home again," she says.

Mornings are the most delightful time to fly, free of the heat of the day, the air smooth and the crosswinds still, afternoon thunderstorms still half a day away. And though some of the breakfasters at Dundee flew Boeing 767s and worked as air traffic controllers in the real world, others were bound by tighter aerial leashes that made a simple dawn patrol an adventure. "Yeah, I remember a while ago making a cross-country in a Cherokee down to Westchester County Airport, near White Plains," one of them recalled. "Two and a half hours down, two and a half days back. Weather moved in."

Yesterday afternoon, when I'd fluttered out of a hot September sky and bounced onto the grass, four local pilots gathered to assess my arrival. They strolled over and politely inspected the garish little Falco while I tied it down. Painted like an Italian military trainer, it turns heads even among old-timer aviators, who invariably maintain a "seen 'em all, flown the crates they came in" demeanor.

"What's she made of, fiberglass? Wood? You don't say! That's a 160 Lycoming? One-eighty? Yuh, she must move right along. Fella up to Penn Yan's been buildin' one of them Glasairs, but it isn't flyin' yet. Where ya based?"

Mine wasn't the only novel mechanism at the Dundee strip. More impressive by far was local craftsman-tinkerer-inventor Clarence Sebring's automatic pancake-making device-officially the Awe-Ja-Magic Machine, so named for his grandson's mispronunciation of its prime attribute. And automatic it by-God is. A large doughnut-shaped steel millstone revolves with stately precision beneath a funnel-like batter dispenser. The dispenser plops forth a dollop of batter every few seconds, and as gears and levers, cranks and cams obediently cycle, each of 15 pancakes makes a lap of the cooker before being flipped by a disembodied spatula onto a new track on the periphery of the hot wheel. Amid the pssssss of compressed air and the hum of an electric motor, another revolution later a scoop briskly slides under the perfectly cooked pancake and tips it onto a paper plate. Complete with a digital counter that tracks the morning's production, plus a "Sebring" logo in chrome script from a 1971 Plymouth coupe-"I go to junkyards and pick them up, put 'em on my various projects," Clarence confided-the Awe-Ja-Magic is a combination of Rube Goldberg monkey-motion and Jean Tinguely artistry, a larger-than-life version of the rolling-balls, tilting-seesaws, racheting-racks machines that the Swiss consider a major artform.

Dundee looked as sleepy as a mutt in the sun, but the first assault on the little farming town's anonymity had been a June 1993 front page Wall Street Journal article, "Flapjack Flipper: Inventor Sebring Has a machine To Do It." The fly-in has grown apace since news of Sebring's automaton spread. "Oh yeah, and we had 'Good Morning America' up here last Labor Day-the broadcast live," enthused Dundee Christmas-tree farmer Joe Sullivan. "And then 'Beyond 2000' came in October to shoot Clarence's machine." Even as we spoke, a TV documentary crew was clamping lights and diffusers onto the weathered joists of the Dundee Flying club's ramshackle row of shed-like hangars, setting up to tape Sebring and his Awe-Ja-Magic Machine.

Meanwhile, the line for breakfast grew faster than the Awe-Ja-Magic's immutable spew, though a backup gang of old-fashioned human pancake-flippers and egg-fryers did a good imitation of automata. "This is the longest line I've ever been in," groaned jonas Dovydenas, a pilot who'd arrived late from Pittsfield, Massachusetts, with his wife Betsy. "There are visa lines in Cuba shorter than this. I figure we're in the fly-in lunch section, and everybody behind us is here for dinner."

Conversations sprang up, war stories got told, Finger Lakes summer yachtsfolk in gaudy slacks chatted with locals wearing feed-store gimme caps, pilots yarned with Harley riders. And yards away, a flurry of small airplanes taxied and blatted, scurried about and parked, and impatiently bounded back into the air. The strip was short and rolling-really just a well-mowed pasture-and the approach from the north over a grove of tall trees was a bit tricky, making perhaps the first 300 feet of the runway unusable. Yet unlike the weekend scenes at mainstream airports, where frenzied inepts bounce and wheelbarrow along with tires screeching, every pilot finessed his or her approach and landing. Hardly a one failed to turn off at the middle of what was essentially a 2,400 foot strip. These weren't weekend Spam-can drivers but flying farmers, experimental-airplane builders, vintage-aircraft restorers, and airline pilots on their day off.

The Cessnas, Pipers, and Bonanzas turned right to park among the corn and alfalfa. The less tractable and more interesting biplanes and taildraggers were signaled left, to primp and pirouette alongside the breakfast line: A Bücker Jungmann in the colors of a German "civilian" pre-war training unit, spindly landing gear as firmly outthrust as the forelegs of a puppy at the end of a leash; a superbly restored Stearman, its 220-horsepower Continental radial chuffing like a steam engine; a silver Stinson 108 wearing the yellow and red roundel of a Spanish Air force liaison plane, even more unlikely than my Falco's phony Italian "Aeronautica militare" costume; and most unlikely of all, a miniature Junkers Ju 87 Stuka, bigger than a large lightplane but little more than half the size of the German dive bomber it aped. Whoever built it had gone to enormous effort to create an exact replica of one of the ugliest, most malevolent airplanes ever produced-a dump truck for bombs.

There aren't many fly-in breakfasts with as long and splendid a history as Dundee's, which has been held twice every year since 1965, on Memorial Day and Labor Day. The Flying Club kitchen cycled through some 1,600 fly-in and drive-in breakfasters last September, and the men in yellow vests parked over 100 airplanes. But if you're planning to attend next memorial Day, you'd better arrive early: Clarence Sebring hopes to introduce a second Awe-Ja-Magic device that he's been perfecting for over a year now. While his flapjack carousel continues its stately dance, his new egg-frying machine will be over-easying a steady parade of eggs, one every seven seconds, the white of each exactly four inches in diameter. Be there.